(From intertitles to multiple language versions)

Another important part of how we watch films has to do with language. How do we watch films that speak a language other than ours? Again, we need to go back to the beginning of film history in order to understand what is available for us now.

When silent films were introduced and became popular, many people thought that finally, and for the first time ever, human beings had created a universal language, one that everybody could understand. Charles Chaplin’s most famous character, the Little Tramp, was at some point in the 20s considered to be the most iconic and recognisable image in the world and viewers in different countries considered him not as a British or American character, but as one of his. After all, he didn’t speak any language.

But this is not exactly true. Most people think that the translation of films started with introduction of sound in cinema in 1927 but actually, silent films also spoke different languages. As early as 1901, silent films started using intertitles, cards with printed text that were included in between images to convey dialogue or descriptions. When films had to be shown to foreign viewers, these intertitles were replaced with title cards in the viewers’ language.

With the introduction of sound, filmmakers and producers had to think of a different solution to translate films. The first one they came up with was very surprising: making the films again and again in many languages, sometimes with the same director and actors, some other times with different actors. They were called multiple language versions. In Paris, for example, the Joinville studio, founded by Paramount, made multiple versions of the same films in up to 12 languages 24 hours a day in 1930.

Of course, this was very expensive, so they soon had to think about alternative solutions to translate films, either revoicing the characters’ speech in another language or translating what they said as text at the bottom of the screen. This is how dubbing and subtitling were born.

(Dubbing)

In dubbing, the voices of the characters are replaced with voices in the translated language matching the lips of the actors on screen. The translation is done by translators and then voiced by dubbing actors working in a dubbing studio with instructions from a dubbing director.

The translators must make sure that the translation is almost exactly as long as the original in order to match the lips of the actors on screen. When there are close ups where only the face of the actors is seen on screen, the task is much more difficult. The translators must then make sure that whenever the actors close their lips (which happens when you pronounce a p, a t, an m, a v and an f), the translation also uses some of those letters to match the lip movements. So, for example, if there is a close up of the face of an actor saying “Good bye” in English, using “Adiós” in Spanish would be a good translation in terms of meaning, but it would not match the lips of the actors, which are closed with the word “Bye”, but not with “Adiós”. Maybe in this case “Nos vemos” (see you later) would be a better option.

Dubbing is the most common translation mode in Spain, France, Italy and Germany, and it is also used all over the world to translate animation and cartoons.

(Subtitling)

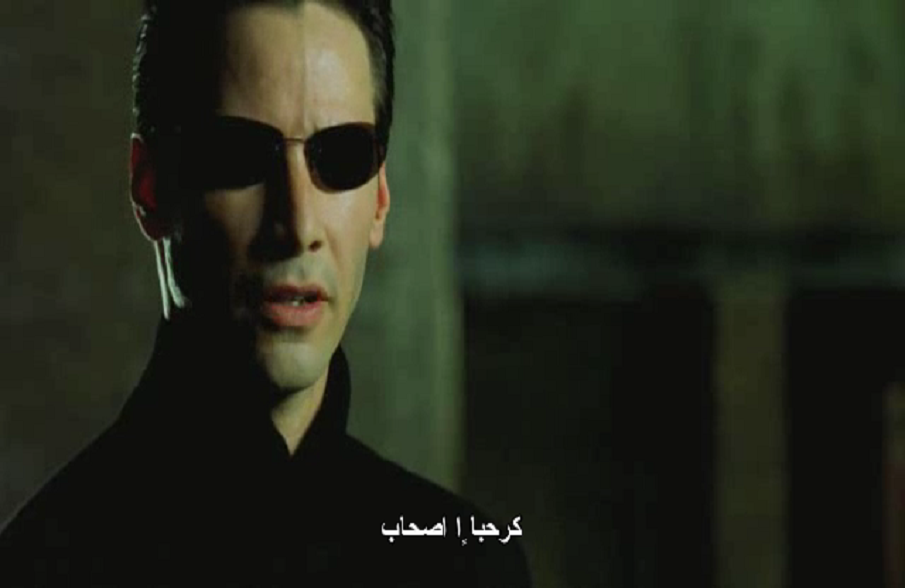

In many other countries, such as Portugal, the UK, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, etc., foreign films are usually subtitled. The viewers in these countries can hear the original voices of the actors and the words are translated normally at the bottom of the screen. Viewers who can understand the original language often complain that what appears written at the bottom of the screen is not always an exact translation of the audio. This is true but we must remember that subtitlers have to follow some rules and they are advised not to use more than two words every second, because otherwise most viewers would find it very difficult to read the subtitles and watch the images.

(Voice-over)

Finally, in some other countries, such as Poland, one person narrates the translation while you can still hear the voices of the original actors. The problem here is that there is only one voice speaking for all the characters and also that this voice doesn’t really show a great deal of emotion, so some of the intensity of the film may be lost.

Producing partner: University of Roehampton http://www.roehampton.ac.uk/home/

Voice Talents: Dylan Ayres, Sharon Fryer

Music: Bensound – Brazilsamba (Composed and performed by Bensound http://www.bensound.com)